Sakhile&Me is pleased to present Gaabo Motho, a group show exploring "home" through works by Wangari Mathenge, Mario Moore, Anike Sadiq and Lerato Shadi. The exhibition will run from March 11 until April 24, 2021. Gaabo Motho is centered around the Setswana saying "Gaabo Motho go thebe phatswa," which loosely translates to "There is no place like home" with an emphasis on a sense of acceptance and nurture from or by the place or the people close to us.

The exhibition invites the audience to meditate on what makes "home" or indeed a sense of belonging. It includes works in still/motion and juggles both sound and silence in videos and paintings that sensitize the viewer as they move though the space and think through the idea of "my/our place," "my/our body" and/or "my/our home." Shadi's, Sadiq's and Moore's videos help us to think through how language and muscle memory store, carry and replicate how one conceives of "belonging," with or to a body, a people or a place. Mathenge's and Moore's paintings highlight the familial connections we draw on as we look to family and close companions for our sense of home: how a gesture, phrase, sensation can indicate that we are safe and our company is desired or we are foreign, ill-fitting and in danger of expulsion.

In the video "Motlhaba Wa Re Ke Namile," Lerato Shadi explores what it means to possess no history and thus to have no future. In the video that was filmed in Shadi's native town, Lotlhakane, she eats earth from her homeland, gags, stuffs more into her mouth and gags again as tears roll down her cheeks. The only part of her that is visible is the section of her face from her cropped eyes down to the shoulder area and the hands that continue to stuff earth into her mouth. The work evokes slave masks that white slave owners placed over the heads of their dehumanized workforce to prevent them from swallowing dirt and thus committing suicide as a last gesture of resistance and an act of escaping one's own body in an attempt to escape a place one does not belong.

Anike Joyce Sadiq's video "Visited by a Tiger" introduces Dr. Daniel Siegal's hand model of the brain, explaining the situation-dependent neurobiological dominance of either conscious or affective thinking and the resulting (re)actions in threatened situations, followed by a psychological reference to stress and trauma caused by exclusion. The work explores in what ways the experience of displacement, exclusion or "not belonging" in a place or with a people manifests in the body, highlighting how the human mind and body react to stress caused by racial microaggressions and why the fight against racism and structures of oppression must also include maintaining mental health. In the words of writer and activist Audre Lorde: "Caring for myself is not a personal luxury. It is self-preservation and thus an act of political warfare."

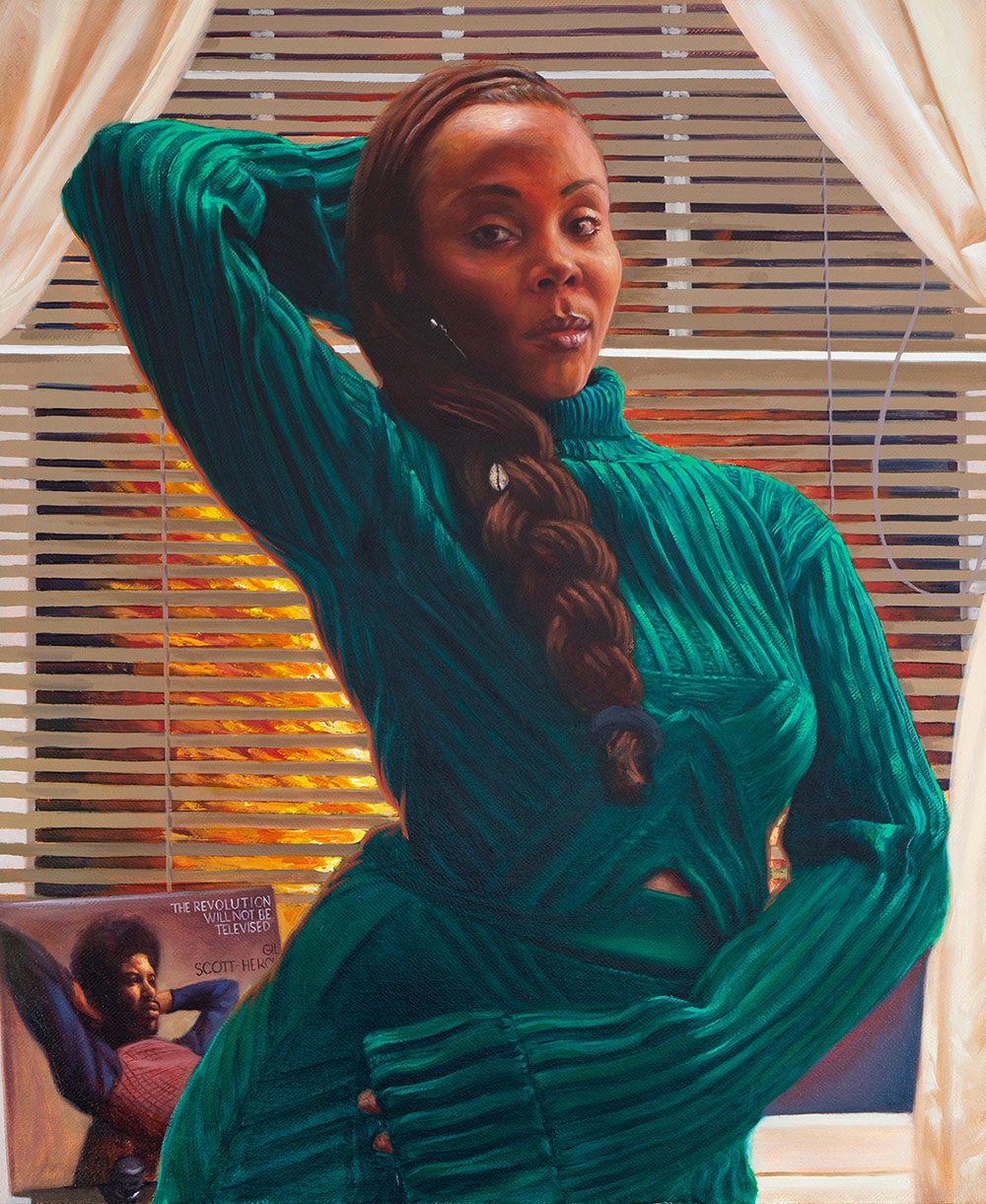

Seen alongside Shadi's and Sadiq's video projections, Mario Moore's work gestures towards a related line of inquiry, asking what repreive, self-presevation and a sense of home look like in a place that is unwelcoming and reads you as foreign or as a threat. Moore's video "I Wish It Were Mine" shows the artist in a cabin, his narration in the background referencing the broken contract between the United States and its citizens who are descendents of slaves, a contract in which the government swore to begin the process of reparations by offering former slaves 40 acres and a mule. Land and property ownership laws have historically bared Black Americans from owning property and the artist meditates on how he wishes the cabin was his. Carrying forward this contrast between the interior and the exterior, Moore's painting "It Might Not Be Such a Bad Idea" depicts his wife inside their home, pictured in front of a window that reveals a burning fire outside. The artist points to struggling to feel at home in a country that makes it hard to feel at home as a Black man, turning to his partner as someone he feels safe with, nurtured by and at home with.

This approach to finding home in others is carried further in Wangari Mathenge's painting "The Ascendants X - Tea O'Clock with Neel's Ringgold." Well known for her portraits and figurative paintings with gestural brush strokes depicting herself and family members in interior spaces, Mathenge's compositions confront issues of visibility and expectation placed on the Black female within the context of both the traditional African patriarchal society and in the Diaspora. Recurring motifs in her work, such as the East African Khanga fabric that adorns tables, cushion covers, couches or is otherwise presented as a decorative rug and the Akamba curio of a Maasai elder, propose a hierarchical significance in their import as 'diasporic objects' and act as mnemonic devices, their overt display serving as a celebration of identity, which in turn aids in the acculturation of the migrant to their adoptive homes.