Portraits of Absentees: Mbali Dhlamini and the Aesthetics of Withdrawal

by Nadine Isabelle Henrich

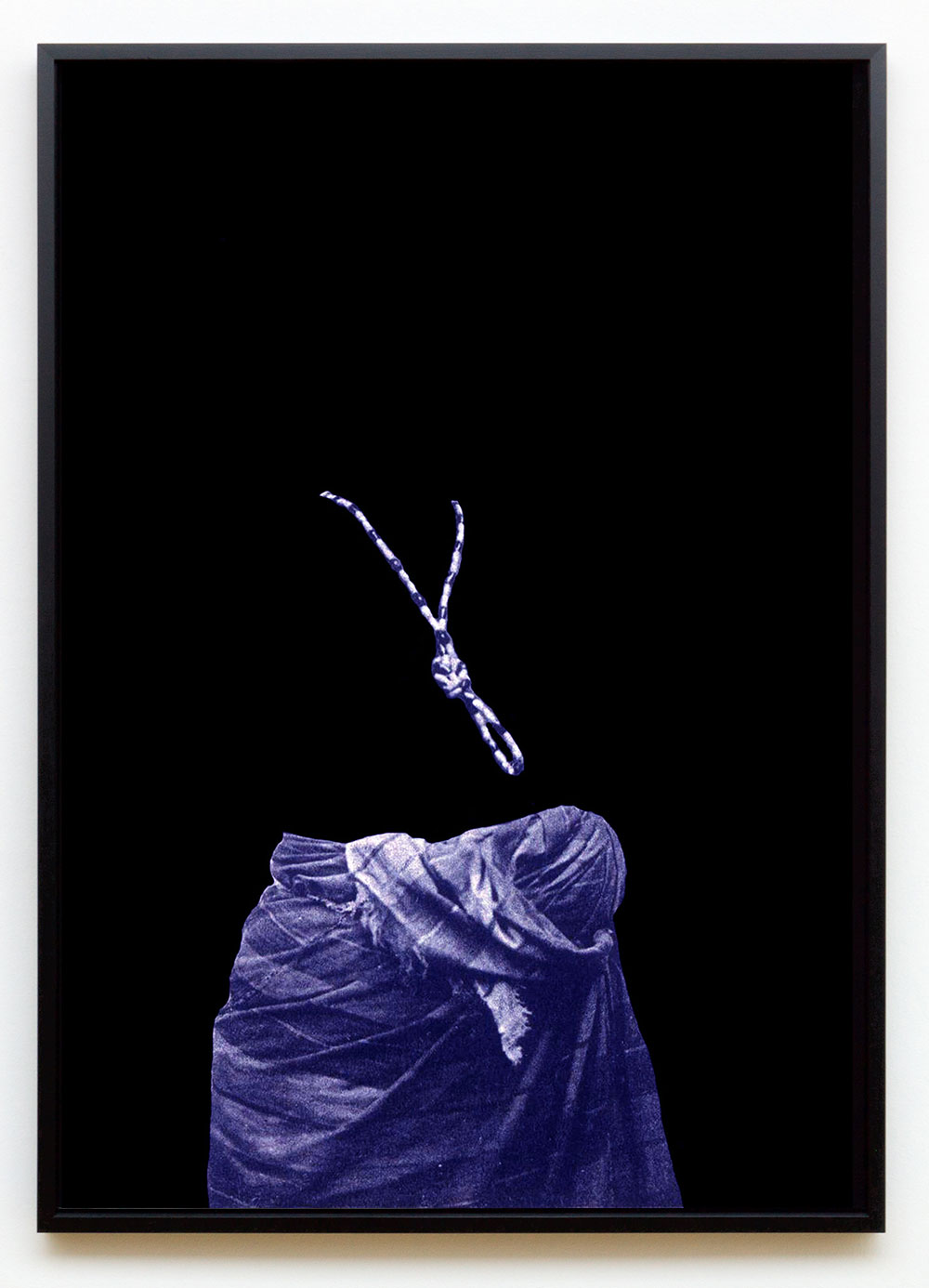

In her artistic practice Mbali Dhlamini embarks herself in an ongoing search for points of contact with pre-colonial identities and spirits. Her search manifests in a spectrum of ex-periences in painting, photography, video, and installation. A monochrome-black pictorial background that absorbs the gaze is her signature motif, consistently appearing in her work since 2013. Dhlamini's portraits, in contrast to genre's definition, persist without a physical presence. Clothes, like empty shells, hint at the former existence of historical protagonists. Dhlamini works with an aesthetic of withdrawal. Her works attest to an on-going, internal conversation with past and present visual landscapes and archives. Her imagery revolves around the question of self, revealed beneath layers of imposed "Western" religion, Christian garments, and attempts to emancipate the black female body from the colonial gaze.

The solo exhibition "Mbali Dhlamini: Go Bipa Mpa Ka Mabele" provides insight into four different groups of works and traces her preoccupation with processes of decolonization and African identity formation. The show departs from the photographic series Look Into, which the artist began researching in 2017 during an artist residency in Senegal. The titles of the large-scale photographic prints "Untitled - Afrique Occidentale, Fille Ouolof" and "Untitled - Dakar, Femme Sénégalaise" reveal geographical, ethnographic and cultural modes of attribution as they were used for photography in the context of anthropology in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Almost like figures of abstracted icon paintings, these women of indigenous West African communities appear in their traditional indigo-colored robes.

During the colonial period in Senegal, French, presumably white, photographers took the portraits that form the source material for Dhlamini's works. The beginnings of French colonization of Senegal date back to the mid-17th century, the time of the founding of the capital Saint-Louis, although official colonial policy through the annexation of Senegalese kingdoms is dated in the 19th century.1 The women, submerged in the unrecognizability of historical spaces, lead us to see the racist penetration of photographic technologies. White skin was elevated as the standard of imaging technology, and the tonalities of black skins were rendered less precisely. In this way, the void of bodies could be read in terms of media reflexivity as well as colonial history.

Untitled - Afrique Occidentale, Fille Oulouf

© Mbali Dhlamini

There is a third possible reading concerning the viewing experience of the edited photographic prints. The artist has digitally reworked the scanned photographs: People and background intertwine to form a black color surface. The portrayed elude the eyes. Only the fabric covering their bodies mark their presence in the black background. The viewer experiences a loss of control. The omission of the human bodies that once filled these fabrics activates the imagination and transforms the act of looking into a process of projection, accompanied by the impression of being secretly observed oneself. The artist's withdrawal of the faces and bodies creates a new situation for the viewer. Looking at photographic portraits is usually linked to a voyeuristic experience, a hierarchical structure that characterizes photographic representations of the female body in particular, and structures the photographic dispositive as an instrument of 'othering' and collecting in the context of (neo-) colonial narratives.2 In Dhlamini's works this power relationship is rearranged. The original distribution of roles between the viewed 'object' and the viewing 'subject' is destabilized. Through her reworking of the photographs, Dhlamini revises mechanisms inscribed in the photographs, the colonial gaze and the exhibiting of black female bodies, and shifts attention to the brightly patterned garments that mediated social codes and held cultural meanings in indigenous communities. In Look Into, as often in Dhlamaini's work, a process of unlearning and relearning takes place in order to question supposedly established knowledge and make visual representations readable in a different way than their historical contexts intended.

The monochrome black background runs as a motif through all the photography-based works as well as the drawings in the solo exhibition "Mbali Dhlamini: Go Bipa Mpa Ka Mabele." In the first room, the female body remains consistently withdrawn from view in the described series Look Into (2017-2021) as well as the two drawings "Untitled" (2021) with wax and synthetic indigo on paper. Like a blank space, an unplayed stage, the individual woman remains a projection. The works activate inner images of the viewer's imagination of the hidden "femme sénégalaise." Thereby they critically evoke the preconception of West African women formed by anthropology and colonial photography in the imagination of white, Central European viewers.

In the exhibition, large-format photographs follow, introducing the color red alongside the presence of the artist herself. In varying poses, the artist sits in profile and is wrapped by a dress of transparent foil. The costume recalls the reconstructed transparent foil dresses that were a leitmotif of her early installation "Bomme Ba Seaparo," from 2013. This work, which she showed at the University of Johannesburg at the time, already marked an artistic exploration of the relationship between the pre-colonial body and the motif of "seaparo" (Engl. christian church vestments). In the work, another semi-transparent figure is superimposed over the outline of the wide foil costume, like a red silhouette. Sometimes the pose of the red form is coherent with the artist's posture, while at other times it is bent down, thus superimposing different moments of a movement. In addition to a sequence of her own postures, the form can be read as a temporal trace of past instances to which the artist relates her present. The specific dress, the "Holy Bible" in the artist's hand, as well as her gaze and body language evoke historical events, such as the forced, missionary Christianization of young women in West and South Africa, among other places. But beyond this colonial instrumentalization of Christian faith, with a view to the history of South Africa, the role of African free churches, as places of cohesion between black communities and the organization and support of resistance against the apartheid regime, must also be pointed out.3

Here, too, a reflexive reading on media-history is possible: photographs were often distributed not only as black-and-white silver gelatin prints, but also as hand- or machine-colored prints and postcards. Photographs from colonial contexts were used for a wide variety of functions, from racist propaganda, to anthropology, ethnology, and historiography, to entertain a white audience through the construction of the "foreign" and the "exotic." the red stencil-like form can be related to those historical reproduction and colorization processes. The uses of photography in conjunction with political, economic and colonial power relations, and as an instrument of "othering," inextricably interweave developments in the history of media and technology with historical, economic, and social dimensions, that resonate in Dhlamini's work.

The video work "ukuhlamba" (2021), whose title in Xhosa can be translated as "to bathe oneself" or "to clean oneself," enhances the sculptural quality of the artist's use of plastic foil. Created in stop motion from individual photographs, the video begins with the artist lying down, largely hidden under her wide foil dress and bonnet. In front of a black background, slow, ritualistic movements take place to an intense rhythmic sound that resembles stroking and rubbing on smooth stone. In the process of the video, a slow, heavy breathing also becomes a central sound motif of the work. As the artist slowly rises to a seated position facing forward under the crunching, rubbing material sounds of her robe, ritualistically cleansing herself, the soundscape mixes with a gospel chant. "Imikhuba yobumyama" (engl. "the way of darkness"), sang by a women's choir. Over the duration of the over four minute long video, the artist's body moves drawing an arc. After the singing and the breathing have faded away and only the stroking and rubbing can be heard, the artist's body returns to its original position, which now appears to be mirrored to the right. The performative enacting of past existences and rituals can be experienced here both dreamlike and contemplative.

Dhlamini's artistic practice is one of transformative appropriation and thereby reorganizes the power relations inscribed in historic material. Using the aesthetics of erasure and transparency she destabilizes the sense of neutrality attributed to photography, particularly in the realm of "documentation" for Ethnology or Anthropology.

Dhlamini's interventions activate the images by "making the portrayed leave the frames" and create a sense of ghostly autonomy of the historic material. From being passive historic archive material the photographs reach a condition of agency and open up to new meanings.

The Capacity of Things: On Mbali Dhlamini's Art

by Athi Mongezeleli Joja

«Within this country where racial difference creates a constant, if unspoken, distortion of vision, Black women have on one hand always been highly visible, and so, on the other hand, have been rendered invisible through the depersonalization of racism. Even within the womenʼs movement, we have had to fight, and still do, for that very visibility which also renders us most vulnerable, our Blackness. For to survive in the mouth of this dragon we call America, we have had to learn this first and most vital lesson — that we were never meant to survive.» – Audre Lorde 1

This essay will attempt to make a fuss about an aspect in South African artist Mbali Dhlamini’s visual art practice that can simultaneously go unnoticeable as it is also conspicuous, namely, the materials she uses and how. Physical art materials are often—nonchalantly—taken as mere nonsignifying organic matter within the chain of creative production of the artistic object. Plastic, cloth, color, language, skin, sound etc.—are some of things used, engaged, and invoked in Dhlamini’s work. In this article I discuss this resourceful consideration of what ordinarily occupies the background—a kind of dead matter? —as an attempt to foreground and affirm its effects. The implicit questions that pervade this exercise is to ascertain what it means to think of the work produced not only in terms of its signification or commentary, but also the substratum base of the materiality manipulated, reconfigured, and repurposed in the process. Much of Dhlamini’s work seems to hinge on and around how black women figure and configure things. Therefore, exploring this proclivity to materiality isn’t just a detached/formalist inquiry into Dhlamini’s artistic process, but also a dialectical reflection on the existential dynamics that her work grapples with.

In a 1972 interview, South African artist exiled to France (since 1938) Ernest Mancoba once insisted that ‘the materials that we use, is the materials of the moment… at the disposition of the milieu, in which the person finds himself.’ 2 Mancoba is arguably making a claim about how excess can lead to creative dereliction by comparatively drawing our attention to how people in the imperial West vis-à-vis certain native and less fortunate communities can rely on less to make impactful cultural artefacts. Obviously influenced by his earlier socialistic view of the world, Mancoba’s position to materialistic privilege in art production and society writ large provides a critique to the logic of capitalist excess without necessarily fetishizing impoverishment as a better alternative. He further opines that ‘in the Occident, we have an infinite choice of material, and the is – do we take the right attitude to this material, in order that this material can respond to our exigence of questioning our destiny.’ 3 This was one of Mancoba’s pet maxims. He repeated these words throughout his long and troubled art career until his death in 2002, age ninety-eight. Although his intensions could easily be mistaken to mean that art materials and the form they cultivated were secondary to the content; on the contrary, his intentions were to sleight the persistent art world’s orthodoxy around conventions that always seem to lead to stereotypes, monopoly and exclusionism. For him, honest art must embody the struggle to constantly break free from what he would call ‘the problem of perspective.’ 4 And although his initial motivation was in reference to or in justification of his formative sculptural predilections inspired by classical European art, the principle would also apply to his approach to painting.

Just as this adoptative and freedom seeking impulse particular to black and marginalized communities in the wake of the colonial encounter informed the overall thinking of the “early pioneers” in modern African art, it would equally inform the next generation of Black modernists that would emerge in the post-war period in South Africa. Take the example of sculpture and anti-apartheid activist Pitika Ntuli, who while incarcerated during apartheid made art using daily prison ephemera like bread and soap. We could say the same about David Koloane, Pat Mautloa, Willie Bester and Mbongeni Buthelezi—though working in different registers—also resorted to non-conventional art materials, to interrogate the political and aesthetical orders of the day. From land dispossession, economic exclusion to the scarcity of art materials, the common thread is the suspension of black social life in which artistic production plays a significant role:

«One needs space in order to prepare a portfolio, one needs access to materials…something to sharpen a pencil with, access to the pencil, access to a bit of flat space which not the cooking surface in the family kitchen…And this, of course, is lacking in most black households.» 5

Recognizing material access has undoubtably become an important step towards social transformation. But so is realizing the fortitude of black artistic production under conditions meant to ghettoize, bastardize, and diminish the cultural integrity of black expressivity. In the post-apartheid era, however, South African artists—particularly black artists—have further experimented with non-conventional materials. In fact, the younger generation of artists would slowly abandon the non-specific, unconventional found objects. With that intentionality and focus, they would turn to more rudimentary but nevertheless materials that have local resonance—cow dung, red ochre, Ghana-must-go bags, “traditional” items, cow horns etc.—in order to cultivate a vernacular expression while at the same time articulating a sensibility with a global reach. But unlike their predecessors who were burned at the stake by critics and/or exoticized by the liberal art establishment, the newer generation of artists participate in a relatively agreeable context and theirs work easily fits into emerging global trends in contemporary arts.

Mbali Dhlamini’s art forms part of the long and protracted evolution of South African, continental, and global artistic experiments that have calibrated diversified aesthetic practices. However, in Dhlamini’s work the materials she uses, as physical properties and media, do not play second fiddle in her creative and conceptual process. In other words, the materials she is using are not simply the local aesthetics conduits, tagging along, in a larger battle for national and personal singularity. Instead, they are constitutive elements of the work; such that, most times, the materials themselves are given self-reflexive power as both object and subject in her art. The materials she is using become the entry point in an endless and ever unfolding drama in which they are content and form. And this latter point, to a great extent, is what considerably distinguishes Dhlamini’s work from her peers. Instead of simply asking the viewer to think with art object’s attempted articulatory grammars of expression, she invites us to think about the technological, affective, sonic and haptical valences of the materiality used as constituent matter requiring and meriting serious consideration in our attempts to think with and from the art object’s “point of view.” This materialist consciousness in the artist’s work begets an interesting discourse to reflect on the enunciatory capacities of things, which interestingly distinguishes itself from the ordinary instrumentalist approach to objects as docile matter at the mercy of the user. Of course, the latent contradictory anthropomorphism should be noted, however, without collapsing the underlying aspirant preoccupation in superseding the hegemonic human-centred approach. To explain the peculiarity of this stance, I would need to briefly try to align Dhlamini’s work to emerging philosophical and critical orientations that have equally assumed this stance, namely, new materialisms and object-orientated ontology.

In recent years we have seen a resurgence of a largely philosophical but nevertheless interdisciplinary orientations, called new materialism, and object-orientated ontology, that have emphasized the analytical as well as ontological value and role of inanimate matter in the world. This scholarship generally poses questions to modernist theories of subject formation and subjectivity, challenging us to wonder about what it might mean to think from the perspective of the inanimate matter. Here the object or thing, isn’t conceived at the distance as the subject’s mute and displayed item of examination—in fact, subject(ivity) itself is suspended, circumvented—but from a speculative end that assumes that this “dialogue” is staged between object to object (human beings included).

From the “perspective” of new materialism, theorist Jane Bennett’s turn to inanimate things, what she refers to as ‘thing-power materialism,’ is predicated in ‘the hope of fostering greater recognition of the agential powers of natural and artifactual things, greater awareness of the dense web of their connections with each other and with human bodies, and, finally, cautious, intelligent approach to our interventions in that ecology.’ 6 The newness of this new materialism relies and extends from the internal critique of the older materialism. Bennett’s criticism, however, shows how this subject-centred approach has led to non-human things to be overlooked in process or merely seen as subservient matter. Her overall stance is predicated on how this contestation reproduces the classical biblical binarism—culture and nature, conqueror and conquered, owner and property, master, and slave etc.—that reinforce the paradigm of alterity and exploitation.

For object-oriented philosophy, on the other hand, this turn to inanimate matter has not just heightened a critical curiosity on materiality but also recultivated the interest in the question of form identified with mid-century discourses on art. Philosopher Graham Harman’s object-oriented ontology places critical interests in the object’s form and therefore its capacity, as opposed to its mere natural and pristine state of objecthood—even accusing the new materialists for not going further enough. In this case, form does not just refer to the external, physical properties of the object but also their functionality and relation with other objects (including human beings). Vacillating between Heidegger and Greenberg’s theories of art, Harman harmonises the form/content fissure characteristic of the last century’s major art debates notably between formalists and social art history—what Bertolt Brecht (responding to Georgy Lukacs) once characterized as ‘formalism on the one side—contentism on the other side.’ 7

However, as art historian Huey Copeland has recently noted a certain critical discrepancy and oversight within this interdisciplinary framework. ‘[T]his affinity’ Copeland writes ‘also pertains to the potential blind spots of the two discourses, which, in the name of universal values and transcendent theoretical schemas, again risk abetting “the social reproduction of white supremacy” through the elision of marginalized perspectives, especially—in the words of Cedric Robinson—that “accretion over generations of collective intelligence” stemming from black cultural traditions.’ 8 To provide explanatory alibi for Robinson’s claim, Copeland reaches for theorist Fred Moten, whose reconsideration of Marx’s famous formulation of a commodity that speaks asks us to rethink the proprietary logics of racial slavery, its assumed mastery over the enslaved and the slave’s furtive resistance against that logic. According to Copeland, Moten ‘has brilliantly shown, certain commodities—in particular, enslaved women—did in fact speak, and sigh, and shriek.’ 9 He continues further:

«Moten’s writing instances a critical orientation toward the sensible rooted in the historical production of black flesh—suspended between sexes and genders, animate and inanimate, person and thing, animal and machine, agent and material— that underlines the porousness of ontological categories as well as the brittleness of Western culture’s epistemological foundations, which time and again place the black body as limit and exemplar, whether captives in the slave-ship hold, specimens on the examining table, or magnetized targets of state violence in the streets.» 10

Pardon me, I’ve digressed! Now back to Dhlamini! We can certainly say that the modern artists’ turn to non-conventional art materiality hasn’t just been an attempt at resisting and dodging the myopic imposition of orthodoxy but also, perhaps indirectly, making a statement on the aspirant elitism found at the conjunction of cultural and capitalist modes of production. What makes the contemporary generation of visual artists in South Africa—in which Dhlamini belongs—so noteworthy, is their diligent interest in marginalized knowledges. Although recently, more pornotropic elements have taken a center stage, artists like Dhlamini have avoided the charms of spectacularity by delicately walking the tightrope of affirming and superseding these paradigms. The procedure at hand for these artists, more so after the student riots (circa 2015) that sparked the decolonial turn, has been about doing the quiet work of locating what Saidiya Hartman might call the scenes where terror can hardly be discerned. 11 Looking into objects or materiality, as a way of simultaneously looking at historical experiences of black women, has been the strategic rerouting that Dhlamini’s work repeatedly dwelled on. This strange but familiar place of material objects and the matter of black feminine presence always already reducible to the property of another, is the furtive and subterranean theme that arguably subtends Dhlamini’s project. In this sense Dhlamini arguably comes close to both Graham Harman’s position of refusing to “undermine” the innately erratic capacity of things and Fred Moten’s insistence on the elliptical “magic of objects” in which blackness is a generative force.

In her earlier works, particularly the installation and photographs titled Bomme ba Seaparo, Dhlamini’s preoccupation is with celebrating the religious women of the African Independent Churches (AIC). Historically, AICs were formed by black religious leaders who either broke away from traditional colonial churches or influenced by the redemptive theology of African American missionaries who frequently visited Southern Africa at the turn of the last century. Although these churches enjoy considerable following and stature today, under the British colonial administration their black nationalist inclinations were menacing. But given the present regime, the term “independent” church is redundant, not because historical justice prevails but simply that the missionary inspired hierarchies (in so as religious sects are concerned) no longer makes denominational sense.

Artist talk with Mbali Dhlamini, Athi Joja, Nadine Henrich & Sakhile Matlhare

Seeing these women walking the streets, particularly on Saturdays and Sundays, in their colorful and immaculate church tunics is a common sight in the South African landscape. In these artworks, one of the significant things artists like Dhlamini repeatedly remind us of and about Bomme, pertains to the pride and confidence within which they wear, command, and perform the assumed honorable individuality these uniforms are said to activate as sartorial emblems of distinguished belonging. Like a sacrosanct layer that can be put on, the sumptuary laws the wearer abides by beckons a certain social decorum, that the onlooker must readily perceive and interpassively enjoy, and they [the wearers] must immediately perform, proclaim, and even exploit. A poetics of relation and a performance of dignity. When she wears her uniform, the churchgoer struts, and swaggers differently, as if simulating a righteousness in their step. If on an ordinary day a person is usually temperamental and cantankerous, the belief and respect given to the tunics, instantly transforms them (at that moment) to immediately align themselves with the assumed righteous personality agreeable to the designs of religious sartoriality. This always requires an extra sense of cleanliness, which often is an external metaphor for the Christian’s supposed interiority. Interestingly, this boundary between inside and outside is as prevalent as it is porous. Church uniforms are therefore performative items: on the one side, they are usually colorful denominational intramural unifiers intended to mask the individual (class) differences among the congregants of the same church and on the other side, a denominational mark of distinction from the rest of the other churches.

There has been rapid interest in the sartorial practices of black working-class women in the last two decades in contemporary South African visual arts. Like the genre painters of the modern era who were fascinated by the exotic, laboring and pious native, not all those who are interested re-presenting black womanhood cast it in a generative light. In his 2003 series, Ticket to the Other Side, white South African male artist Beezy Bailey—in collaboration with photographer Zwelethu Mthethwa—is in blackface and dressed up as a black woman he christened Joyce Ntobe, whom he situates in several social and domestic mise-en-scenes including as domestic worker and churchgoer in AIC uniform. On the other end, the works of two South African artists Senzeni Marasela and Mary Sibande isolate the political and cultural meanings of clothing to unravel underlying social ills. Taking her mother’s dress as entry point, Marasela opens a pandora’s box on the largely ignored question of women’s histories of migration under apartheid. By way of drawings, performance, and mixed media works, Marasela oscillates and stitches together discordant relations between past and present, mother and daughter etc. to trace the strenuous itineraries of black women and their stories of ‘beautiful dreams whose pieces lie shattered at the dreamer’s feet’ in foreign lands. 12 Perhaps the closer work to Dhlamini’s, is Sibande’s 2009 piece, I Put a Spell on Me. In this piece Sophie—the avatar adopted by the artist to construct a fantastic and conspicuous sculptural imagery of the largely peripheral figure of the black maid—is here seen with her arms stretched out in a prayer-like gesture while also holding a religious staff, typically used in AICs. Unlike in her usual elaborate Victorian work attire, here Sophie is seen wearing a rather ostentatious version of the AIC church uniform. In short, with both artists we can clearly see the artistic and feminist precedence on how black women artists use sartorial practices to make social commentaries.

The Bomme ba Seaparo photographic series is an interesting example of how Dhlamini turns to materiality and matter not only to critique the racial and gendered regimes of colonial visuality, but also participates in an ecology of knowledge that takes African spirituality and the nurturing centrality of black feminine power in it very seriously. Like in the case of Marasela and Sibande, the dress becomes a central motif in which the black women’s experiences are particularly engaged. As an installation, Bomme depicts a transparent hard plastic material resembling the religious garments of the church that kind of feigns a procession of ghostly figures suspended space and time. Here we encounter a double negation, that is in the form of the absent human body and the absence of the tunic. In other words, does the African body and foreign tunic exist by way of a substitutive regime of representation which (strangely) does not lead to cancellation but, maybe, as an attempt to negotiate the terms of their potential co-presence? The translucence of the plastic becomes the material instantiation of this paradoxical logic of an absent presence or present absence, a matter that stages invisibility through its inevitable visibility. But also, the plastic negates itself through its own material affirmation as mediated lack. In its luxuriating ebbs and flow of the drapery, it becomes excessive. But this excess is the surplus of nothing, a paradoxical infinite multiplication of deficiency.

On this dialectic of excess and lack and colorfulness and decoloring, we certainly can’t avoid to simultaneously think of the sounds these materials (the plastic) make. Listening to the material isn’t just paying attention to legible and/or illegible narratives we garner in their display but also in mobilizing all our senses. In isiZulu, the word “imizwa” speaks to the activation of sensory receptivity in the body. Central to this piece is precisely this multi-sensory distribution and reception activated at level of sight and sound. These suspended plastic robes subtly absorb and translate the acoustics of the space into abstract percussive fractures and subtle whistling. The sound of plastic in the wind can emit a gentle sound, almost like a whistle from afar. But to properly “see the sound” in photographer Roy DeCarava’s sense, we must turn to the photographic representations of the tunics. 13 What is interesting here is that Dhlamini “sculpts” the plastic material and then photographs the static object as moving. The circular, twirling movements found in some of these churches known as “isikhalanga” isn’t only a central liturgical expression, but one also deeply musically bound. It is these Sufi-like circular movements that Dhlamini captures here. Photographically, however, the plastic takes on a new abstracted dimension. Seeing the sound refers to the phonic emissions of the carefully molded plastic, frozen in a photographic moment of a gestured movement.

While in this series, we begin to see Dhlamini’s propensity for materiality through the serial re-moulding and modelling of the plastic sheets to resemble corporeal figuration without actual human figures. In the subsequent series, this quest for matter and materiality is pushed further. In her graduate show titled Non-Promised Land, Dhlamini reopens the investigation into black religious material culture by turning to its symbological realms of color and/as language. Here color speaks to the linguistic and therefore cultural criteria of the symbological imaginaries that articulate certain spiritual and moral concerns—greens, blues, yellows, whites, and reds forms a stable palette that enact a different chromatic ordering to the racially inflected and hypostasized logic of color that the colonial missionary discourse introduced. The pastel drawing series Bomma (2015) turns on the variegated, garish religious garments of AICs: unlike the previous works briefly explored above, Bomma directs its attention to how color guides the spiritual realms and ecclesiastical orders of the church. Put differently, what retains more significance here is that color, as material and symbolic artefact, is engaged not necessarily for its aesthetic instructions in the visual field but also for its spiritual and symbolic efficacy in the religious practices of these churches. In these pieces, the uniforms readily jump in their full and crisp chromaticity as if suspended on a hanger. And yet there’s something about their figurative comportment that makes them seem worn and occupied by a human body.

But what do we make of the pervasive absence of the body? On the one hand, we must say something about how Dhlamini quietly militates against or deviates from the faddish traffic of black figuration enacted in contemporary arts. (But for purposes of space, we will not pursue that line). On the other hand, we must ask: is this visual gesture an affirmation that black flesh is “nothing,” a mere “empty suit” to use a common English expression? This is a moot point considering that in western visual culture (which Dhlamini’s work interrogates) racial blackness is a menacing category. As Audre Lorde notes in our opening epigraph, to depersonalize black people—black women in particular—racism needs black flesh present and/or re-presented. You may ask what is about black flesh that enables it to occupy multiple registers and loci, that is, be present but absent or be absent but present. Perhaps to understand this point we might have to return to Dhlamini’s use of the plastic materials as metonymic matter underscoring the racist uses and abuses of black flesh in the order of being. If the reader remembers; above, we argued that plastic materials contain the oscillatory capacity to negate itself through affirmation or affirm itself through negation. This paradoxical logic of absent presence becomes a strategic suspension of the body, a ghostly trace rather than corporeal materiality, which is visually apprehended by its effects and occupation in the church uniforms. This absenting seeks to visually counteract the negative plasticization of blackness in the scopic regimes of colonial visuality. In the words of Zakiyyah Imam Jackson:

«Plasticity is a mode of transmogrification whereby the fleshy being of blackness is experimented with as if it were infinitely malleable lexical and biological matter, such that blackness is produced as sub/super/human at once, a form where form shall not hold: potentially “everything and nothing” at the register of ontology.» 14

Dhlamini’s visual interventions aren’t necessarily unprecedented but rely on familiar tropes and motifs that make part of our everyday worlds. She relies on commonplace materials and identifiable elements to draw our attention to matters commonly ignored. Take still Life; that is, how it relies on everyday objects and ephemera to make broad social statements. Human life is understood through the things and objects that surround it. In other words, the absence of human presence is always already presumed. This is a mere illustrative point. But Dhlamini might be on to something else—that is, her drawings aren’t adventures into the pictorial world of still life, representation of inanimate objects notwithstanding. Her refusal to re-present comes closer to portraiture than to still life, however by denying portraiture the sitter’s face—a visual phenomenon curator Laura Firstenberg calls an “anti-portrait.” As Firstenberg has taught us, black artists also turn to these strategies to critique the racist undercurrents of the visual field.

Similar to the Bomma series in which the human body is physically eliminated, Dhlamini’s recent solo show Go Bipa Mpa Ka Mabele (2022) with the Frankfurt based gallery, Sakhile&Me, the featured drawings and photographs looks into sartorial materials albeit this time, investigating the many uses of the indigo plant and cloth dyeing tradition in Senegal—a research project she did during her artist residency in that country. This brings us to the importance of process in Dhlamini’s work. The idea that each work bleeds into another, in a serial way, speaks to both the relentless and archeological aspects of her work. The indigo works are perhaps the raw examples of her general approach to her art making.

In the same body of work, Dhlamini also returns to the subject of black women and materiality with a more striking feature this time around, namely, the presence of her physical body in the work. Here she retains the plastic garment initially used in the photographic series Bomme ba Seaparo but drops the focus on color of the uniform to explore a newer set of questions. The central piece of the show was a stop-motion video installation titled Ukuhlamba (2020) and accompanying set of photographic stills, which she tweaked and edited to precision. In the video, the plastic garment isn’t necessarily the dress that it was before, but simulates a body of water in which the figure is either soaked in or unraveling from. The process of ukuhlamba isn’t necessarily the same as baptism, even when baptism is the commonplace purgative process in Christianized contexts. In fact, in most AICs, Baptism is the precondition to the newly converted required prior to them wearing the religious garments associated with their spiritual re-awakening and purgation. On the one hand, people are baptized as individuals and only ones in their lives. Ukuhlamba, on the other hand, can also refer to spiritual and collective cleansing of, say, a home or community after a disaster, in which members of the group plead with the ancestors to remove the cloud of darkness. It is a process that can be and is repeated several times in ones’ lifetime. In other words, ukuhlamba is a form of detoxing, both curative and preventative; it anticipates the events and responds to them by way of decontaminating the individual and the collective body. Thus, the African reference to ukuhlamba—unlike in the Christian baptismal ceremony—is a continual process of cleansing and reflection. As the title of one of her photographic stills, An Ode to Ukuhlamba (2020) might suggest, Dhlamini’s performative enactment celebrates this ritual and culture of healing.

In the photographic pieces, particularly the work Meetlo and the diptych Bugubedu, Dhlamini uses the plastic material as a malleable and elastic product only to bring the viewers’ attention both to the derived message as well as the form in which she delivers it. The artist has chosen her own body as the site of reflection and ocular interest. But, at the same time, using her plastic material tunic to tentatively, if alluringly, conceal parts of her body by obscuring, tempering and abstracting it. At the level of form, Dhlamini transmogrifies the plastic as well as anthropomorphizes it in Meetlo. Meetlo means custom in Setswana. Indigenous language are rarely the objects of interests to be explored in visual arts. Dhlamini occupies this vacant terrain, often using the combination of written and visual language to allude to (if not altogether elude) forms of cultural translation. Latent in the visual exploration is the importance of color, which the diptych Bugubedu (red) explores. For example, the wearing of red and white orche during rites of passage usually signifies liminal and transitional phases that requires a specific transformative reconfiguration of the body. In other words, this isn’t simplistic inquiry on the sociology of color, i.e., red means blood and so on. In Bugubedu, the figure is captured in a state of transient wakefulness and becoming. This becoming is not always detected merely in rites of passage, say, from boyhood to manhood, but also exemplify the total outlook of African philosophical thought that motion is the essence of be-ing. 15

These two photographs also bleed into each other in the ways in which motion, language, color and illusion are the central themes. In other words, meetlo also alludes to mahlo, which basically translates to eyes or seeing. In Meetlo, for example, we can see an androgenous and multilimbed body seated like a yogi and resembling the Hindu deity, Shiva. The body is redoubled into several other figures in a Matrix move. But the central figure is Dhlamini herself, facing directly at the viewer as she’s covered by plastic. The sense of movement and stillness typical of Shiva’s imagery, is a playful masquerade between allusion and illusion—a custom of revealing and masking typical to African and non-western cultures. Within this highly animated moment of gesticulation, at the core of the figure we “see” a glim formation of the “eye.” The role of language in this process is important and proposes the customary relation between meetlo and mahlo, or better, the dialectical interdependence between the people and their culture. What you see or hear is not always what you get. This complexity in non-western cultural customs instantiates constant departure from the proposed, by way of ritualistic forms of metonymical representations of social life.

Unlike the works we spoke about before, in this body of work the black body is present, visible but nevertheless still dodging and eluding full scrutiny. It is vagued and obscured by the plastic materials whose irregular folds and draperies that “protects” it from our perusal. The works exhibited here show the rapid maturation of Dhlamini’s project and her knack for sustaining various tangential issues within the same conceptual rigor sustained from formative works. There’s something interestingly scholarly, which is not necessarily the same as academic, in how Dhlamini has pursued her work thus far. She has diligently explored her “object matter” with the kind of archaeological curiosity and persistency that has shown generosity and experimentality. Therefore throughout this essay we have tried to explore the complex visual language that Mbali Dhlamini employs in her work, however without didactically feeding the reader with fixed meaning of what certain artworks might mean or necessarily say. This avoidance is strictly to leave room for the reader to use the tools employed here to enter this visual universe that Mbali Dhlamini has created for us and engage it in their own subjective terms.